Given China’s status as the world’s second most populous nation and an economic powerhouse, it represents both a monumental market opportunity and a dynamic arena of challenges for pharmaceutical products. With its rapidly evolving healthcare system, limited transparency of public information, and language barriers, China has never proven to be an easy market for overseas pharmaceutical companies to enter. Thus, this article aims to outline the healthcare system and key market access pathways that are opening in China for pharmaceutical products, including vaccines. Additionally, it will delve into the current trends and challenges that pharma companies need to consider when devising successful market access strategies for this unique market.

Despite the disruptive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, steady growth has been evident in China’s pharmaceutical market and research environment. From 2017 to 2022, the Chinese market witnessed a growth rate of 5.3%, compared to the average market growth of 6.6% in the top five European Union markets and 7.1% in the U.S. market (source: IQVIA MIDAS, May 2023).

At the same time, a “drug lag” persists in China for global pharmaceutical companies’ products. Between 2017 and 2021, the median time difference between the first global approval and the approval in China was five years1. Furthermore, the Chinese government maintains its support for local manufacturers to bridge the gap left by innovative foreign drugs or to substitute them with more cost-effective local alternatives. These factors collectively necessitate that foreign pharmaceutical companies develop more comprehensive market access strategies for the Chinese market.

National Basic Medical Insurance

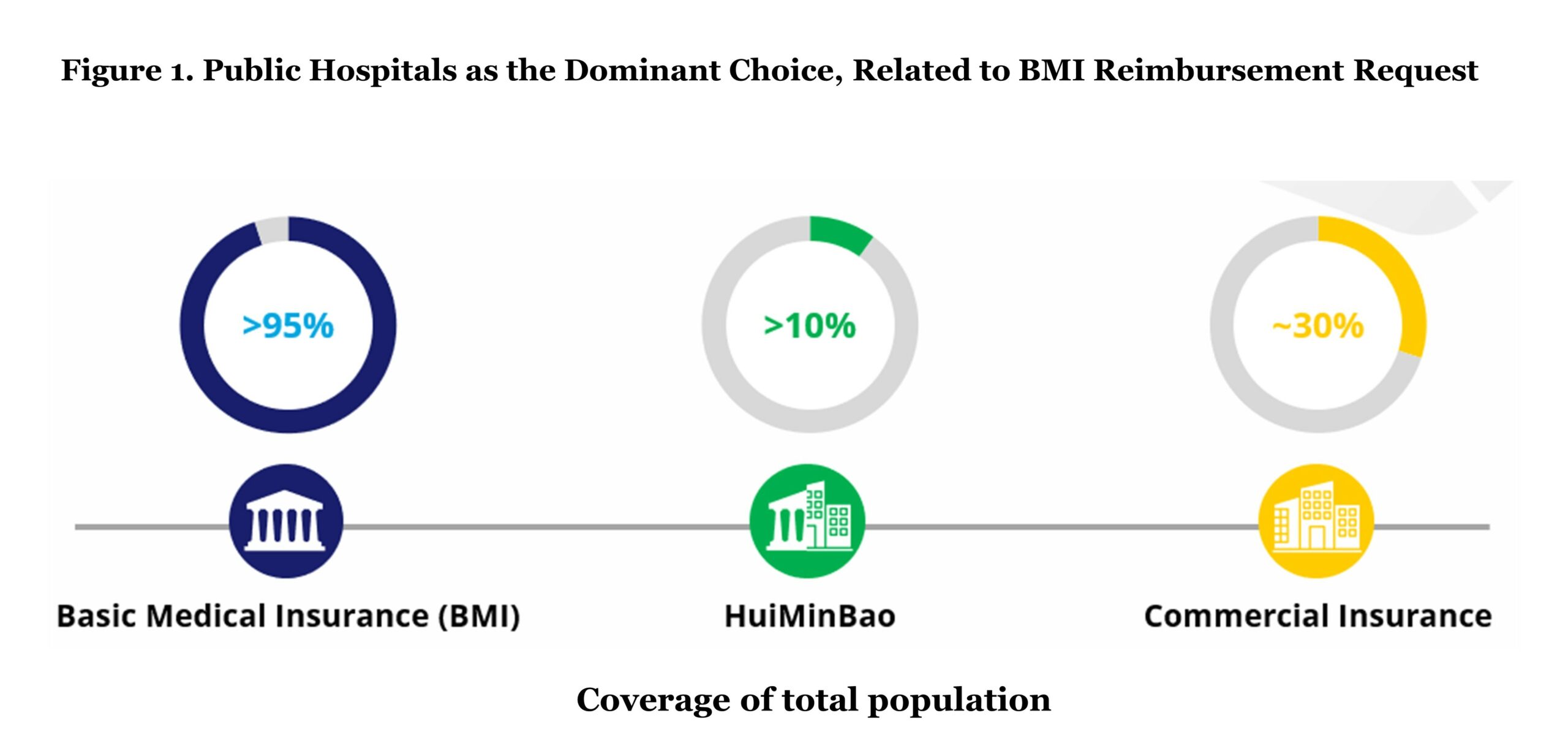

Over a period of 20 years, China has established its universal healthcare system and achieved a coverage of over 95% of the population (approximately 1.33 billion people in 2023). Basic Medical Insurance (BMI), the public insurance that is organized and funded by the government, covers nearly all Chinese citizens. BMI has two types of basic medical schemes: Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI) and Urban and Rural Residents Medical Insurance (URRMI). UEBMI covers all employees in the formal sectors, and it requires contributions from both employees and employers. The population outside of UEBMI, such as children, the elderly, and rural residents, are eligible to enrol in the URRMI scheme. Funding of URRMI is collected from the premiums of the residents in these rural areas and government subsidies. As the centralized public health insurance plan, BMI coverage presents the biggest opportunity for pharmaceutical companies in terms of eligible population size.

HuiMinBao is a hybrid insurance that is funded both by regional governments and private commercial insurance companies and acts as supplementary coverage for specialty drugs and high-cost medical bills outside of BMI coverage. Due to its subsidies from the local governments, HuiMinBao is relatively cheaper compared to commercial insurance. Based on 2021 data, HuiMinBao covers more than 10% of Chinese citizens, which is approximately 140 million individuals.

In 2021, the out-of-pocket (OOP) cost accounts for 28% of the whole healthcare expenses compared to 15.4% of the EU average. Due to the relatively high proportion of OOP payments, limited innovative drugs in the formulary of the BMI (National Reimbursement Drug List), and less treatment location options, commercial health insurance has become more popular in recent years, at least for those who can afford it. Commercial health insurance nowadays covers around 30% of Chinese citizens, mainly high-medium income populations in urban areas acting as the complement coverage to costs that are not provided in the BMI.

Three Categories of Hospitals

Three Categories of Hospitals

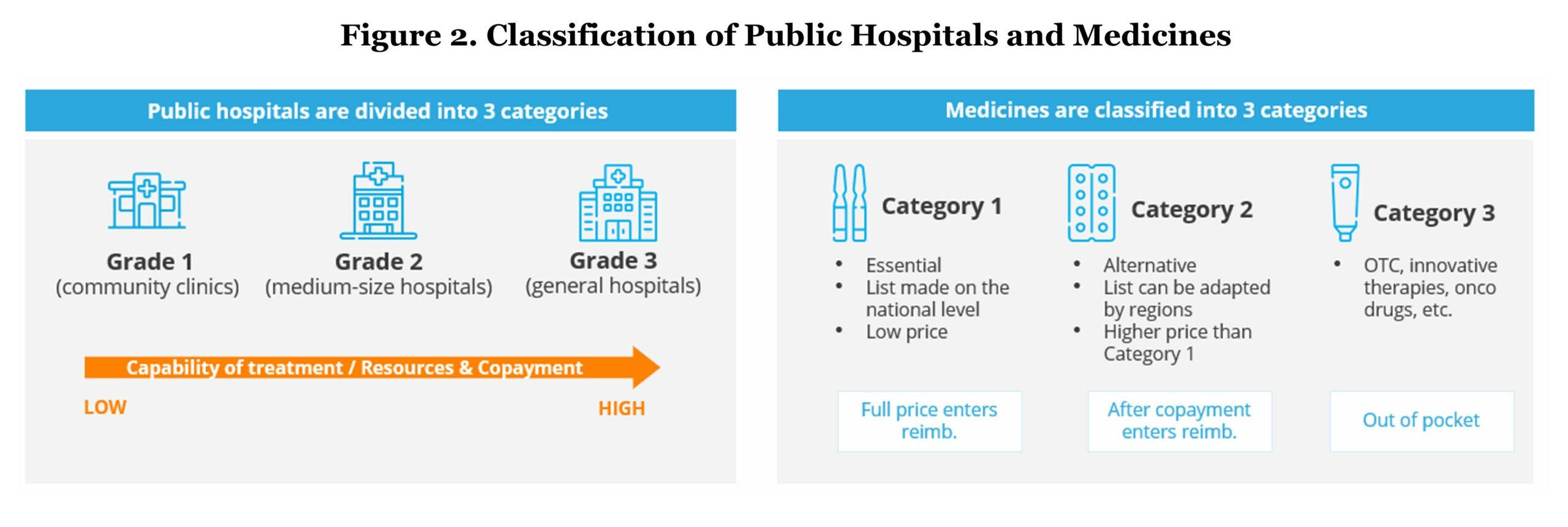

Public hospitals in China have been classified into three grades based on the hospital’s ability to provide medical care, medical education, and conduct medical research:

- Grade 1 refers to community clinics which mainly provide basic medical services including chronic disease management, routine check-ups, and vaccinations.

- Grade 2 refers to medium-sized hospitals generally providing comprehensive health services and medical research on a regional level.

- General hospitals, which is classified to Grade 3, have the highest capability of treatment and medical resources. They offer the most comprehensive health services and perform a bigger role in terms of medical research.

The out-of-pocket (OOP) percentage for the same service is lowest in community clinics and highest in general hospitals.

Three Categories of Drugs

Medicines entering the Chinese market will be classified into three categories:

- Category 1 refers to medicines listed on the “National Essential Medicine List” and are eligible for full reimbursement by BMI. These medicines are considered essential because they meet key public health needs and tend to have low prices.

- Category 2 consists of medicines that are alternatives to the ones in Category 1 but have a higher price. The list of medicines in Category 2 are eligible for reimbursement by BMI but it requires a co-pay which varies by region (average of 30%). This also includes some innovative drugs in rare diseases and oncology with relatively high prices.

Medicines that are not listed in either Category 1 or 2, such as over the counter (OTC) and other prescription therapies (pembrolizumab, CAR-T therapy, etc.), are classified into Category 3, which is not under BMI coverage and requires full OOP payment. Approved drugs that target rare diseases, are used in specific treatment centers, and do not have comparable drugs in the same category form an exception and can be reimbursed regardless of being in Category 3 by some regional HuiMinBao or commercial insurance schemes.

Reimbursement Procedure of BMI Insurers

Although China is working towards providing public coverage for 100% population, the reimbursement policies vary among regions due to the “localized management” principle which indicates that BMI is mainly coordinated at the regional or city level.

Pursuing the reimbursement from the local region is a mix of direct deduction of the BMI-insured services/drugs from their personal medical insurance account and paying the extra services/co-pay part/non-reimbursed drugs OOP, if any.

However, a cross-regional medical visit reimbursement can be more complicated. For example, insurers who seek cross-regional medical treatment have to go through a cumbersome reimbursement procedure. Insurers are required to start with receiving approval from the insured region, and then pay all the medical expenditures in advance at the designated hospitals in their current residence. Finally, once the cross-regional treatment visit has finished, the insurers have to return to the healthcare security administration of the insured area to handle a series of burdensome procedures for filing for reimbursement. Plus, the duration of reimbursement is relatively long, which adds additional inconvenience to the process.

Overall, the reimbursement policies of BMI are highly complex and depend not only on the region but also on the category of hospitals and medicines in which the care is received.

Market Access, Accelerated Approval Accompanied by Increasing Price Pressure

Market Access, Accelerated Approval Accompanied by Increasing Price Pressure

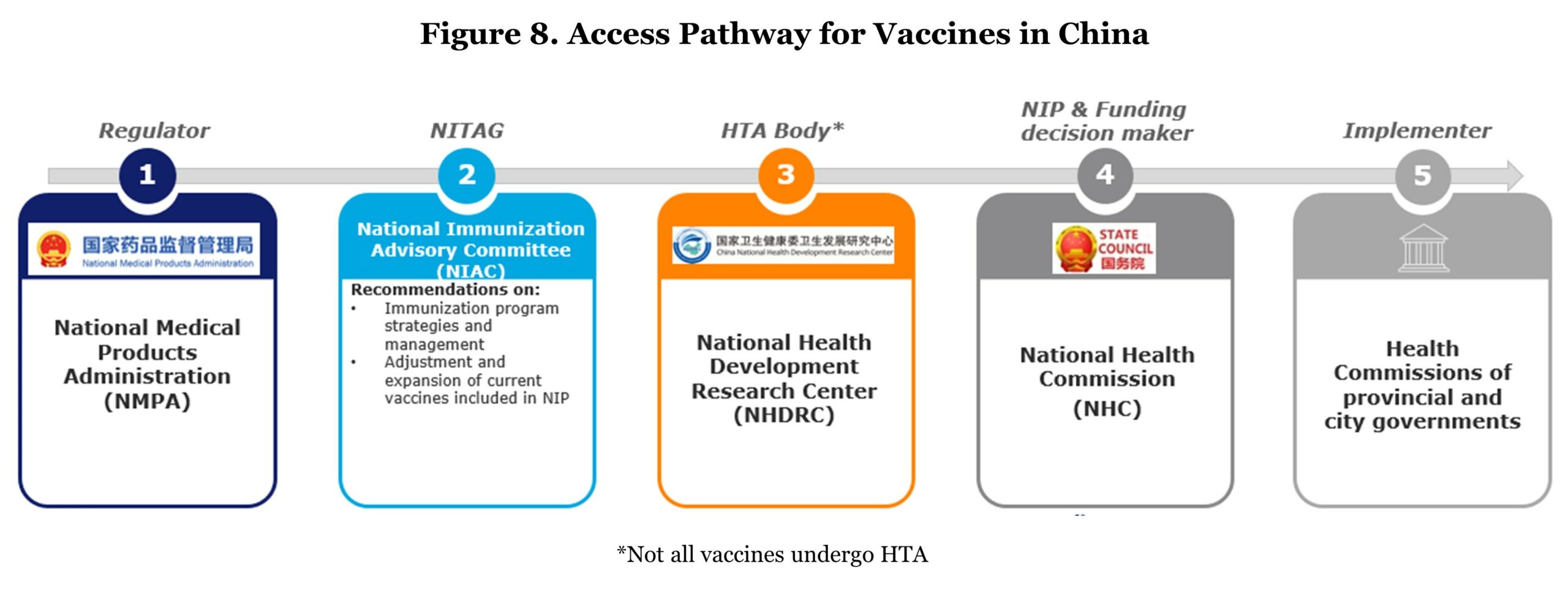

The key stakeholders in the public healthcare system in China include the National Health Commission (NHC), the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA), the National Healthcare Security Administration (NHSA), and the National Health Development Research Center (NHDRC).

- Policymaker – NHC: NHC is responsible for implementing healthcare policies and decisions.

- Regulatory body – NMPA: all pharmaceutical products sold in the Chinese market need to be granted market authorization by NMPA. This requirement is applicable to imported drugs, domestically manufactured drugs, medical devices, and consumables.

- Public payer – NHSA: NHSA is responsible for the administration of the public reimbursement system. NHSA selects the drugs to be reimbursed and forms the reimbursement list called the National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL). The NRDL renewal is conducted annually.

- HTA body – NHDRC: NHDRC is a national research institution with a remit to provide technical consultancy advice to health policy-makers, carrying out research and application of evaluation standards, evaluation quality control, evaluation methods, and process specifications.

Though the drug lag has existed for a long time, in recent years the NMPA has been working on accelerating the approval of innovative drugs. In most cases, imported innovative drugs cannot apply for local regulatory approval with global multicenter clinical trial results and a Chinese phase 3 clinical trial is mandatory. However, this requirement does not apply to orphan drugs for which the NMPA grants an accelerated approval process.

Though the drug lag has existed for a long time, in recent years the NMPA has been working on accelerating the approval of innovative drugs. In most cases, imported innovative drugs cannot apply for local regulatory approval with global multicenter clinical trial results and a Chinese phase 3 clinical trial is mandatory. However, this requirement does not apply to orphan drugs for which the NMPA grants an accelerated approval process.

Since orphan drugs are defined as drugs that are used in rare or orphan disease diagnosis, prevention, or treatment, it is important to understand what is recognized as a rare disease in China, which is determined by The Joint Meeting of Chairpersons of National Rare Disease Academic Groups. In 2021, a consensus was reached that classified rare diseases as those with an incidence of less than 1 in 10,000 newborns, or a prevalence of less than 1 in 10,000 adults, or a patient population of less than 140,000 in total.

Early market access of pharmaceutical products has two pilot zones: the Hainan Boao Lecheng International Medical Tourism Pilot Zone and the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA). In these pilot zones, foreign innovative products can be sold without NMPA regulatory approval. Pharmaceutical companies can sell drugs with free pricing in the GBA and Hainan Boao after obtaining foreign approval (e.g., FDA or EMA) and if the “Lecheng Medical Products Administration Bureau” recognizes the status of “clinical urgency.” Additionally, these drugs also need to prove that there are no available alternatives.

The Hainan Boao Lecheng International Medical Tourism Pilot Zone allows manufacturers to collect Chinese real-world data to be used as supplementary evidence for NMPA registration. Currently, over 300 products have been introduced in this pilot zone with numerous products progressing to gain NMPA approval, such as pralsetinib and dinutuximab beta.

The GBA gives patients access to innovative drugs (e.g., Anti-D immunoglobulin injection) that have been approved in Hong Kong but has not been approved in the mainland China. These innovative drugs can only be used if the significant clinical benefit and urgent needs can be demonstrated.

Nevertheless, the costs of these pilot drugs will be not eligible for BMI coverage and patients may need to pay fully OOP. Early access to the GBA and Hainan Bao will not guarantee success in accessing the mainland China market nor regulatory approval by NMPA. A local phase 3 clinical trial is inevitable for the majority of indications, except for rare diseases. However, manufacturers can start collecting real-world evidence from the early access programs in the pilot zones to enhance the drugs clinical value in local population and support its regulatory application for mainland China.

National Reimbursement Drug List (NRDL) by NHSA

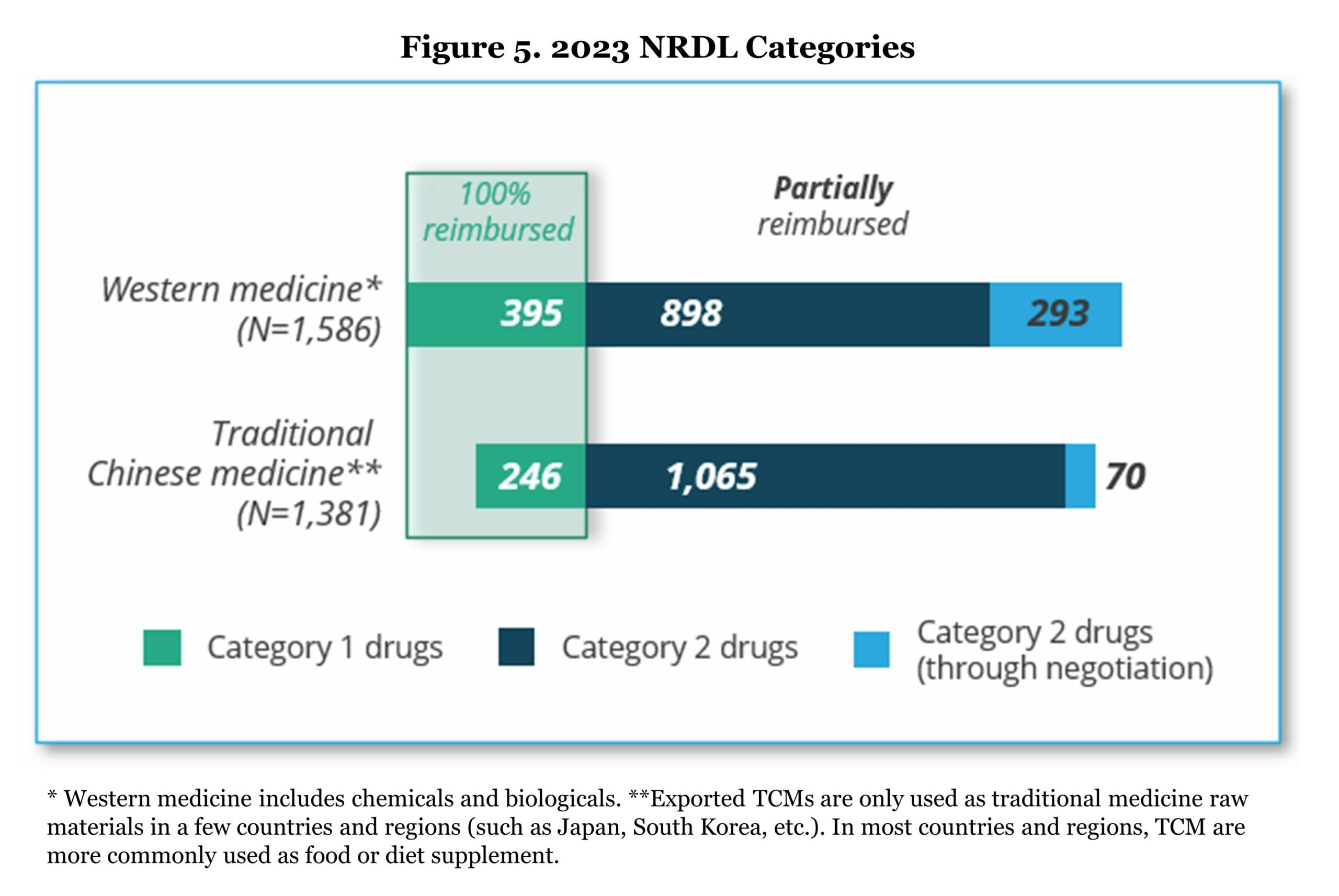

NRDL is the only reimbursed list for BMI plan in China. All provinces must follow the NRDL for drug reimbursement since 2019 without the opportunity of adding extra drugs to the reimbursement list. The current NRDL (March 1 – December 31, 2023) covers 2,967 drugs including more than 100 new drugs for chronic diseases, tumors, anti-infectious, and rare diseases indications. As mentioned in the previous section, NRDL drugs include fully reimbursed drugs (Category 1) and partially reimbursed drugs (Category 2). The drugs in the list are both Western medicines and traditional Chinese medicines.

All drugs in the standard Category 1 and 2 stay in the NRDL with no need for reassessment/renegotiation. However, a small portion of Category 2 drugs (363 drugs in 2023) under the NRDL negotiation category will need to go through a reassessment of the budget impact during the contract phase every two years until being included in the standard Category 2 list or removed from NRDL. In the 2023 NRDL, 121 drugs succeeded in the negotiation and bidding among 147 participants (success rate of 82.3%).

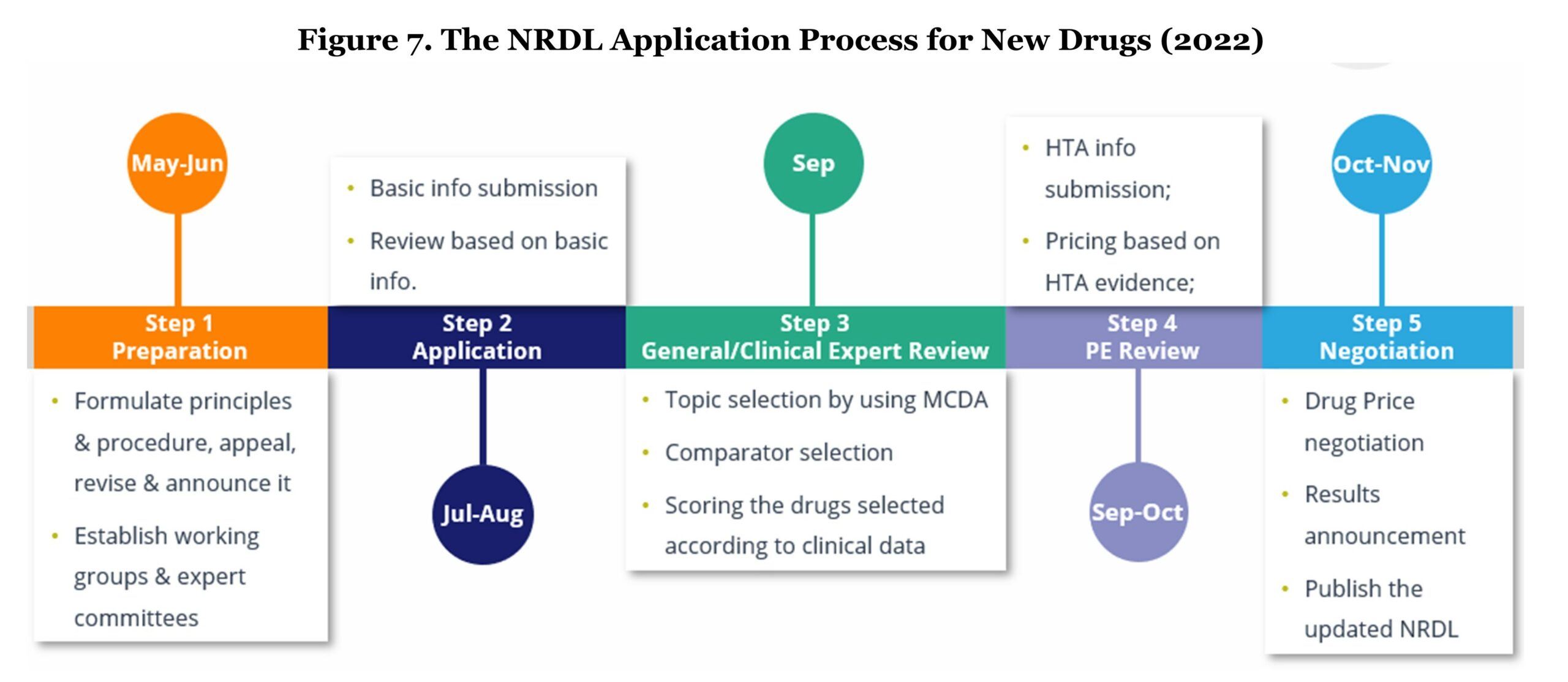

The entire NRDL inclusion procedure for new drug listing starts from May to November every year; therefore, new medicines need to receive NMPA approval before June 30th of the evaluation year in order to be eligible for NRDL negotiation. The evaluation process involves five key steps: 1) Preparation, 2) Application, 3) General/Clinical Expert Review, 4) Pharmacoeconomic Review, and 5) Negotiation.

The entire NRDL inclusion procedure for new drug listing starts from May to November every year; therefore, new medicines need to receive NMPA approval before June 30th of the evaluation year in order to be eligible for NRDL negotiation. The evaluation process involves five key steps: 1) Preparation, 2) Application, 3) General/Clinical Expert Review, 4) Pharmacoeconomic Review, and 5) Negotiation.

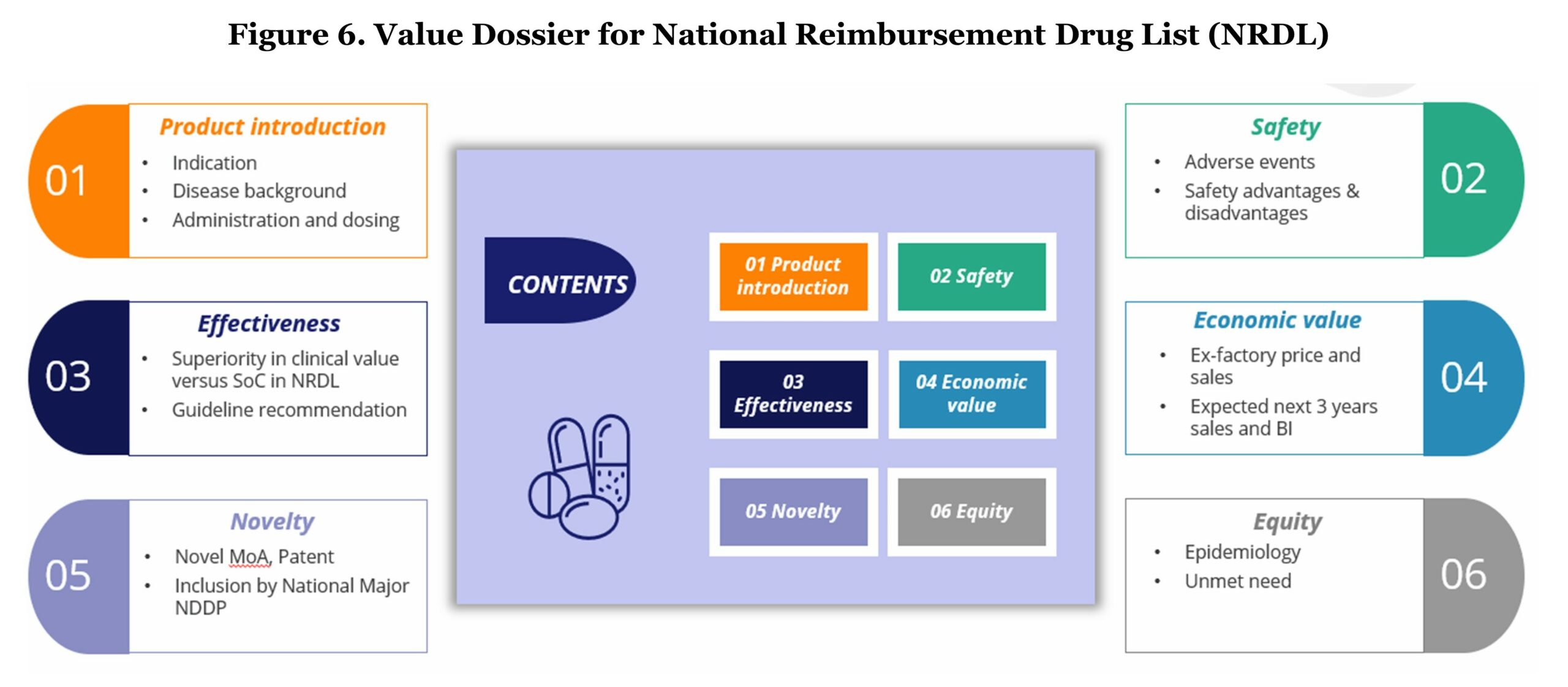

During the application stage, manufacturers should formulate principles and prepare a value dossier which is structuralized in a similar way as a classic payer value story. The content of the value dossier should consist of product introduction, effectiveness, novelty, safety, economic value, and equity.

After the submission, applications will first go through an initial review with the possible outcomes of “pass,” “additional material required,” or “fail.” The following steps involve a comprehensive review which is done by a group of professionals including clinical experts, pharmacists, health economists, and specialists in healthcare funding. They will assign a score to each drug that is deemed to offer additional clinical benefits and that addresses high unmet medical needs. The assessment score will directly impact future price negotiations. Key assessment criteria are treatment effectiveness versus comparators that are currently on the NRDL list, and whether it is the most frequently used option in clinical practice (particular interest when there is no consensus on the most effective option on the NRDL).

Before price negotiation, health economists and specialists in health funding will calculate a “WTP (willingness to pay) price” based on the previous score given by the clinical experts’ and determine an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). The health economists and the specialists will work separately but in parallel. Both groups will meet at the end of their evaluation and compare their determined prices in order to conclude the WTP ceiling price.

Before price negotiation, health economists and specialists in health funding will calculate a “WTP (willingness to pay) price” based on the previous score given by the clinical experts’ and determine an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). The health economists and the specialists will work separately but in parallel. Both groups will meet at the end of their evaluation and compare their determined prices in order to conclude the WTP ceiling price.

On the day of negotiation, experts are grouped and assigned products to be negotiated. The pharmaceutical company will be unaware of the WTP ceiling price and will initially propose a list price in the first round to NHSA committee representatives. If the manufacturer’s price exceeds 115% of the WTP ceiling price, the pharmaceutical company is given a second opportunity to propose a lower price compared with the first round. If the second offer still fails to achieve equal or lower than 115% of the WTP ceiling price, the negotiation is concluded without success. In the event a price falls into WTP ceiling price range, the expert group continues negotiating with the pharmaceutical company until an agreement is reached.

In the 2023 NRDL, the price reduction of 108 newly added drugs outside the previous NRDL reached an average of 60.1%, which is roughly consistent with last year.2 However, rare disease drugs show the tendency of more significant price reduction pressure during negotiation compared with other chronic disease drugs. One of the most significant price reduction cases comes from Roche’s Evrysdi. In 2023, Evrysdi (risdiplam powder for oral solution), indicated for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in paediatric and adult patients, experienced a substantial price reduction of 94.08%, dropping from 63,800 RMB to 3,789 RMB to enter the NRDL. This may indicate that even with more than a 90% price reduction, the expected market in China for SMA can still be attractive for manufacturers to enter. To protect International Reference Pricing (IRP) of these innovative drugs’ prices in other markets and not be impact by Chinese NRDL prices, manufacturers can request to keep the Chinese NRDL price confidential. Overall, entering Chinese NRDL is a trade-off of volume versus price when taking into consideration the massive market size of 1.4 billion citizens.

Vaccines: A More Closed Arena

In China, the current national immunization program (NIP) includes 15 vaccines (all for childhood) which are grouped into two categories. Category 1 (NIP) vaccines are mandatory and free of charge to all eligible recipients while Category 2 (non-NIP) vaccines are voluntary and paid OOP.

The cost of NIP is not covered by BMI, which is managed by NHSA, but financed directly by the NHC. Due to budget control, the market of Category 1 vaccines is dominated by local producers with low prices. Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conducts annual volume-based procurement with a bidding system for all NIP vaccines. While for non-NIP vaccines, the procurement is carried out by provincial and county CDCs. In order to enter the Chinese vaccines market, many foreign vaccine manufacturers seek partnerships with local companies.

Regarding the access pathway, a mature vaccine assessment system has not been built yet. Only two vaccines (pneumococcal and human papillomavirus vaccines) were subject to HTA.3 Speaking of assessment, the vaccine recommending body, Chinese NITAG, National Immunization Advisory Committee (NIAC) was newly founded in 2017 with the aim to advise on immunization policies and update the national immunization schedule. Though China has expanded its immunization schedule, vaccines against four of the 10 vaccine-preventable diseases recommended by WHO are still outside the NIP (i.e., PCV, HPV, Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), and rotavirus vaccines).

Regarding the access pathway, a mature vaccine assessment system has not been built yet. Only two vaccines (pneumococcal and human papillomavirus vaccines) were subject to HTA.3 Speaking of assessment, the vaccine recommending body, Chinese NITAG, National Immunization Advisory Committee (NIAC) was newly founded in 2017 with the aim to advise on immunization policies and update the national immunization schedule. Though China has expanded its immunization schedule, vaccines against four of the 10 vaccine-preventable diseases recommended by WHO are still outside the NIP (i.e., PCV, HPV, Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib), and rotavirus vaccines).

The implications for overseas manufacturers: since the vaccine assessment system is not mature yet, China is not like EU5 or the U.S. where achieving recommendations brings a high possibility of success in reimbursement. In addition, the reimbursed vaccines are primarily provided by local players. Therefore, the target market should be the Category 2 vaccines where there is not much pricing pressure. Especially with the growing purchasing power of Chinese urban habitats, commercial plans and private clinic visits are becoming more common as complements for the BMI, where flu vaccine, HPV vaccine, and Shingles vaccine are often provided.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the dynamic landscape of the Chinese healthcare system presents compelling reasons for pharmaceutical manufacturers to consider venturing into the market. The establishment of pilot zones, coupled with streamlined regulations such as real-world evidence integration and exemptions for orphan drugs, significantly lowers barriers to entry. The well-defined approval process not only expedites market access but also provides a clear roadmap for manufacturers.

China’s acknowledgement of a drug lag, especially in the absence of local alternatives, opens avenues for international pharmaceutical companies to introduce innovative therapies. The sheer size of the population not only offers a vast market but also the potential to offset concerns about lower pricing. Leveraging the ability to not make public NRDL prices becomes a strategic advantage and protects international prices that would otherwise be impacted via IRP.

Moreover, the nation’s commitment to enhancing intellectual property (IP) protection adds a layer of security for companies entering the market. Health reforms aimed at driving innovation further create a conducive environment for pharmaceutical companies to contribute to and benefit from the evolving healthcare landscape. Importantly, the flexibility to enter the market at various levels, be it through public or private channels, provides adaptability to diverse business models.

In essence, China’s healthcare ecosystem emerges as an attractive arena for pharmaceutical manufacturers, offering a blend of regulatory facilitation, market potential, IP protection, and opportunities for innovation. As the nation continues to prioritize healthcare reforms, the landscape remains dynamic, providing an optimal environment for strategic investments and partnerships.

References:

1. Su L, Liu S, Li G, Xie C, Yang H, Liu Y, Yin C, Chen X. “Trends and Characteristics of New Drug Approvals in China, 2011-2021.” Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2023 Mar;57(2):343-351. doi: 10.1007/s43441-022-00472-3. Epub 2022 Nov 2. PMID: 36322325; PMCID: PMC9628473.

2. http://www.nhsa.gov.cn/art/2023/1/18/art_105_10081.html.

3. E. Tomaszek, A. Kapusniak, C. Rémuzat, Y. Onishi, M. Toumi. “PIN36 Comparison of Vaccine Market Access Pathways in European and Asian Countries.” Abstracts From ISPOR Asia Pacific 2020, volume 22, supplement, s55, September 2020.

4. Zhang X, Zhang L. “The Impact of Instant Reimbursement of Cross-Regional Medical Services on Hospitalization Costs Incurred by the Floating Population-Evidence from China.” Healthcare (Basel). 2022 Jun 13;10(6):1099. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10061099. PMID: 35742150; PMCID: PMC9223039.

5. http://www.news.cn/world/2023-04/18/c_1212138541.htm.

6. Macabeo B, Wilson L, Xuan J, Guo R, Atanasov P, Zheng L, François C, Laramée P. “Access to Innovative Drugs and the National Reimbursement Drug List in China: Changing Dynamics and Future Trends in Pricing and Reimbursement.” J Mark Access Health Policy. 2023 Jun 13;11(1):2218633. doi: 10.1080/20016689.2023.2218633. PMID: 37325810; PMCID: PMC10266112.

7. Liu J, Yu Y, Zhong M, Ma C, Shao R. “Long Way to Go: Progress of Orphan Drug Accessibility in China from 2017 to 2022.” Front Pharmacol. 2023 Mar 8;14:1138996. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1138996. PMID: 36969835; PMCID: PMC10031016.