A breast cancer drug from AstraZeneca and Daiichi Sankyo now has FDA approval to address a brand new category of the disease, a decision that enables the targeted therapy to reach a much broader patient population.

The drug, Enhertu, was initially approved to address cancers characterized by the abundance of a protein called HER2. The drug made waves in June during the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, where clinical trial investigators presented data showing that treatment with the drug also helped patients whose cancers had low levels of HER2—levels previously thought to be too low for any therapies designed to target that protein.

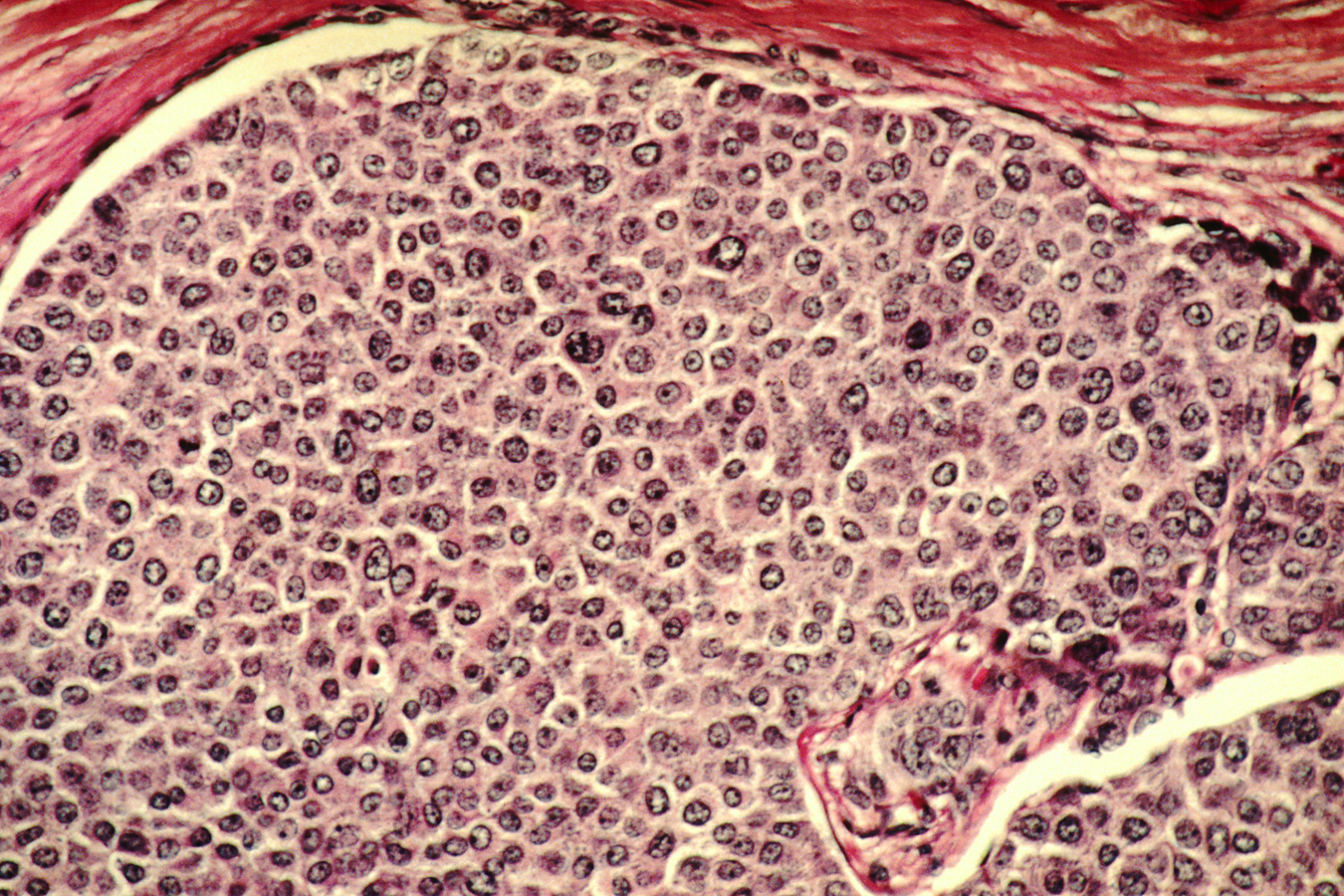

Rather than being classified as HER2 positive, patients whose cancer had low levels of HER2 were classified as HER2 negative, making them ineligible for any targeted therapies. It’s not a small group. Of the estimated 287,850 new cases of female breast cancer that will be diagnosed in the U.S. this year, the FDA said 80% to 85% will be considered HER2 negative. Of those, about 60% can be considered HER2 low. The treatment options for these patients are endocrine therapies and chemotherapies.

In approving Enhertu for so-called “HER2-low cancers,” the FDA is defining a new subtype of breast cancer. The Friday approval also makes the AstraZeneca and Daiichi Sankyo drug the first targeted therapy for this new HER2-low group. The decision was a fast one, coming less than two weeks after the companies announced that the FDA had accepted the drug application and would evaluate it under priority review. A regulatory decision was not expected for another four months.

“Today’s approval highlights the FDA’s commitment to be at the forefront of scientific advances, making targeted cancer treatment options available for more patients,” Richard Pazdur, director of the FDA’s Oncology Center of Excellence, said in a prepared statement. “Having therapies that are specially tailored to each patient’s cancer subtype is a priority to ensure access to safe and innovative treatments.”

A Deep-dive Into Specialty Pharma

A specialty drug is a class of prescription medications used to treat complex, chronic or rare medical conditions. Although this classification was originally intended to define the treatment of rare, also termed “orphan” diseases, affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US, more recently, specialty drugs have emerged as the cornerstone of treatment for chronic and complex diseases such as cancer, autoimmune conditions, diabetes, hepatitis C, and HIV/AIDS.

Enhertu is part of a class of cancer therapies called antibody drug conjugates (ADCs). These drugs are like smart bombs for cancer. They’re made by linking a targeting antibody to a tumor-killing drug payload. Enhertu links the antibody trastuzumab to deruxtecan, a drug that damages cellular DNA to cause cell death. The targeting ability of the antibody is meant to keep healthy tissue from being exposed to the therapy’s toxic effects.

The FDA’s new Enhertu decision is based on the results of an open-label Phase 3 study that enrolled 557 adults. Those participants had advanced HER2-low breast cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. According to the results, the trial achieved the main goal of showing improvement in progression-free survival, which is how long patients live without their disease worsening.

Though Enhertu’s targeted effect is intended to spare healthy tissue, ADCs still come with side effects. The most serious adverse effect reported in the clinical trial was interstitial lung disease, a condition that leads to scarring and inflammation in the organ. The drug’s label carries a black box warning that cautions clinicians about this risk. The label also flags potential toxicity to embryos; the drug is not recommended for those who are pregnant. The most common adverse reactions reported in clinical testing included nausea, fatigue, hair loss, vomiting, and constipation.

Shanu Modi, a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and the lead investigator of the study, said at the ASCO meeting that for most patients, the lung problems that stem from Enhertu were low grade and reversible. She said the best way for clinicians to provide Enhertu is by selecting the patients most appropriate for the therapy and monitoring for lung problems, then managing them if they arise.

Enhertu was initially developed by Daiichi Sankyo. That Japanese company began a partnership with AstraZeneca in 2019; later that year the drug won accelerated FDA approval for treating advanced HER2-positive breast cancers that have not responded to at least two earlier HER2-targeting therapies. Under the partnership, the two companies share in the development and commercialization of Enhertu worldwide, except for Japan where Daiichi Sankyo holds the drug’s rights. Earlier this year, the FDA approved use of the drug as an earlier line of therapy, a decision that converted the accelerated approval to a standard one.

Public domain image by the National Cancer Institute