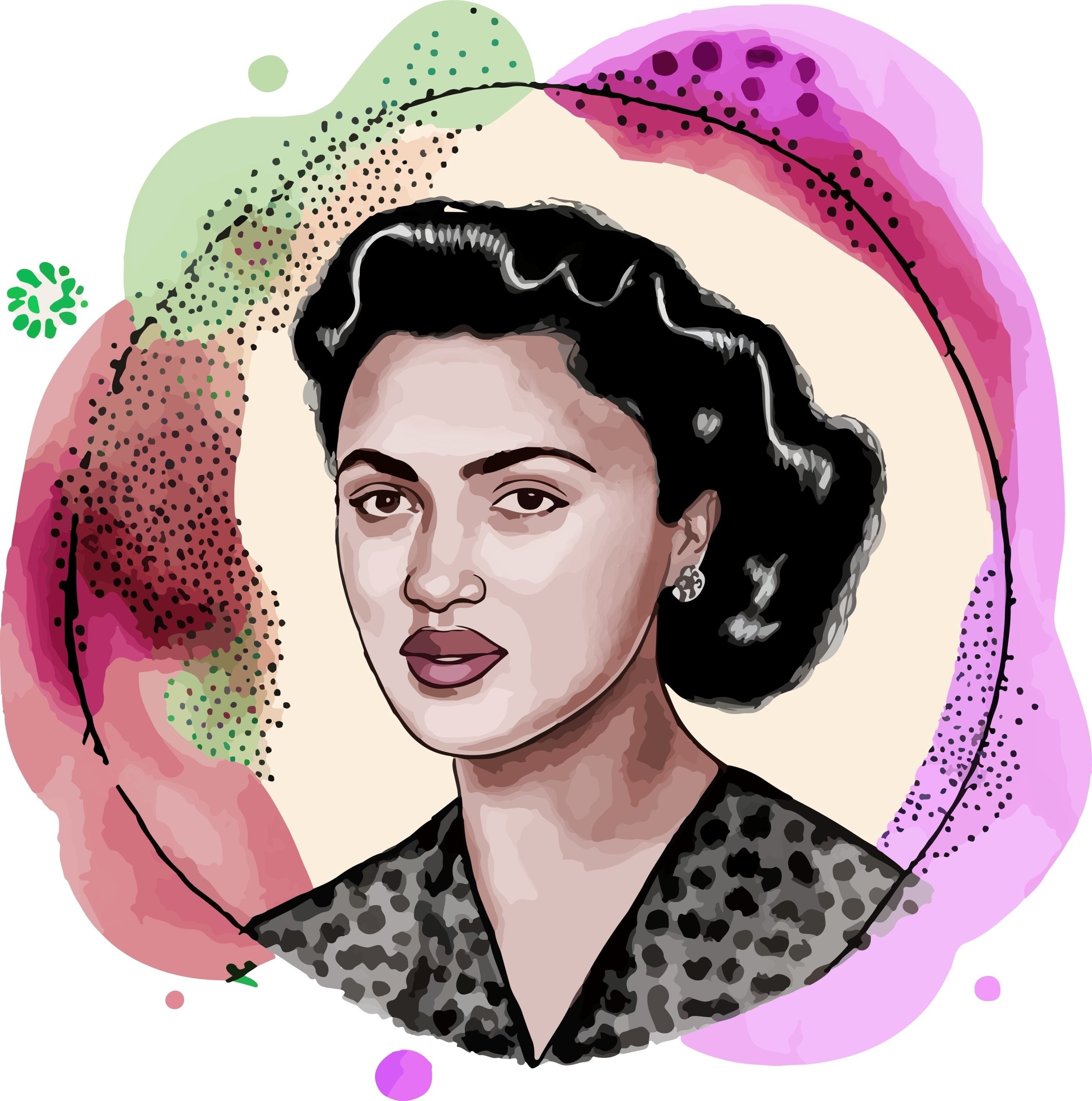

Earlier this month, the family of Henrietta Lacks reached a settlement with the biotech company Thermo Fisher Scientific over the company’s use of Lacks’s “immortal cells”. Lacks was an African American woman who passed away due to cervical cancer in 1951. A cell line, dubbed HeLa, propagated from a sample of Lacks’s cells, were harvested without her consent, and remain in use to this date.

The confidential settlement between the family and Thermo Fisher was the first time her descendants received compensation for the widespread use of the cells. The family has also since filed a new lawsuit against the rare disease company Ultragenyx, alleging that the company “has made a fortune by using Mrs. Lacks’s stolen cells as a factory to make its proprietary gene therapy products.” Ultragenyx is developing several gene therapies, including one named UX701 for treating the genetic disorder Wilson disease.

In an interview with Pharmaceutical Technology, Dr. Robert Klitzman, director of the Masters of Bioethics program at Columbia University, New York, talks about the recent settlement and the questions this case opens within the wider bioethics field.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Adam Zamecnik [AZ]: What do the ongoing lawsuits between Lacks’s descendants and pharma companies mean for the wider pharma industry?

See Also:

Robert Klitzman [RK]: The [lawsuits] raise several important questions. The Henrietta Lacks case involves a terribly unfortunate situation that happened to a poor African American woman whose cells were taken and used for research without her knowledge. Various pharmaceutical companies have earned billions of dollars off her cells, while members of her family have lacked health insurance. In part because of what happened to her, regulations have changed and cells are thus no longer taken from patients without their consent. So hopefully, another Henrietta Lacks case won’t happen, at least in the United States.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalDataAZ: Can we expect more lawsuits on behalf uninformed donors and their descendants?

RK: There are still larger questions facing the pharmaceutical industry related to the case—whether the Henrietta Lacks case sets any precedent, and a larger question about whether people who donate their biospecimens should receive any compensation. In the US and in Western European countries, we don’t believe in buying and selling organs or blood. But some people may say that since Lacks’s family got money for donating her cells, they are not going to participate in research unless they too are paid.

It is important to include diverse patient samples in research. However, people of colour have faced disparities, overall had worse healthcare, and may want compensation. Lacks’s descendants deserve compensation since some of them lived in poverty while companies profited off of their ancestor’s cells. But the extent and form of the compensation remains a question for itself.

We expect people to be willing to donate their biological samples for research for free. The problem is that many drugs are being developed that such people can’t afford. So, people are donating cells for research but will never be able to afford drugs that are consequently developed. If we want people to donate their samples for free, the quid pro quo should ideally be that they can somehow afford the treatments that result.

AZ: John Moore, a leukemia patient, previously sued the University of California for the property rights to his own cells and the court voted in favour of the University. Why was Lacks’s settlement different?

RK: In the Moore lawsuit, the California court decided that once your cells leave your body, they are no longer your property. Hence, the court ruled, Moore didn’t have a claim to the profits from use of his cells.

But DNA and cells don’t fit into the kind of legal frameworks that have historically been used in property law, which was was developed in the 1700s when property was land. There wasn’t much ambiguity about such a physical entity. Now, however, we have cells that can replicate. And if you have my DNA, you then have information not only about me, but also about my relatives. It becomes trickier. As our knowledge and use of genetics become more sophisticated, the concerns at stake change.

The cases of John Moore and Henrietta Lacks also differ because of larger political and social contexts. Due in part to the Black Lives Matter movement, there is much more awareness now about the extent of racism in society, including in healthcare. That may be another factor in the companies being sued and their decision to settle. The lawyer representing the Lacks family quite explicitly argues that these companies have engaged in racial exploitation. And there’s heightened concern about that now.

AZ: Should some patients perhaps feel concerns about participating in research?

RK: There are a few issues here. Will some patients feel exploited and taken advantage of? They very well may. Will they file a lawsuit? At some point someone will, but what will be the outcome? I can’t predict that.

At the end of the Obama administration, the federal government altered regulations covering research allowing investigators to obtain a single-time broad consent from study participants for future use of biological specimens. At some point, I would be concerned that a donor will feel that they didn’t quite understand that or doesn’t like how their sample was then used.

Researchers need to be very careful with such single-time broad consent and not use biological samples they’ve acquired in ways that might harm a group, by stigmatizing the group, for instance.

AZ: In a 2017 New York Times op-ed, you said the advent of new genome sequencing technology makes navigating ethical issues more challenging. Has this changed?

RK: Researchers are getting lots of biological sample data that could be used for patients’ benefit. But participants are not paid, even though [the research] may lead to huge profits for companies. I would be concerned that patients may not fully understand their samples are being used for a wide variety of purposes. 23andme, for instance, sells its dataset. People don’t realise that, and backlash may occur.

With informed consent, we try to have participants understand that donation has social benefits. But a lot of people don’t understand this. For instance, when people participate in research, they may give a biological sample that undergoes genomic sequencing, but [the participants] may not be provided with the results alongside an explanation. Yet some patients very much want these results. So, there’s a lot of room for misunderstandings, which could lead to disappointment, frustration, and conflict that could lead to lawsuits. The bottom line is that the better the informed consent, the better off study participants and researchers will all be.

AZ: Finally, how do economic and health disparities, between companies and individual participants, and among marginalised groups, govern ethics in biomedical research?

RK: There have been huge disparities in healthcare between the rich and poor. The US has wider disparities than many other countries. That’s a major problem that we need to confront. We need to think about all the stakeholders involved, including, for example, insurers, and how we can all address these problems. Companies earn billions of dollars, but the people who donate their specimens are not able to obtain treatments developed. Ethically, that is unfair and needs to be faced.